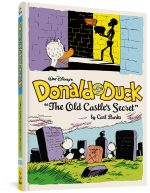

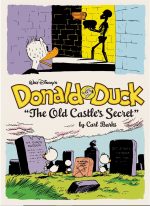

By Carl Barks & various (Fantagraphics Books)

ISBN: 978-1-60699-653-9 (HB/Digital edition)

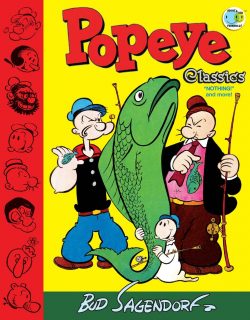

Donald Duck ranks among a number of fictional characters who have transcended the bounds of reality to become – like Sherlock Holmes, Tarzan, Popeye and James Bond -meta-real. As such, his origins are complex and convoluted. His official birthday is June 9th 1934: a dancing, nautically-themed bit-player in the Silly Symphony cartoon short The Wise Little Hen.

However, that date is based on the feature’s release, as announced by distributors United Artists and latterly acknowledged by the Walt Disney Company. Recent research reveals the piece was initially screened at Carthay Circle Theatre in Los Angeles on May 3rd, part of a Benefit show. The Wise Little Hen officially premiered on June 7th at the Radio City Music Hall in New York City, before the general release date was settled.

The animated cartoon was adapted by Ted Osborne & Al Taliaferro for the Silly Symphonies Sunday comic strip and thus classified by historians as Donald’s official debut in Disney comics. Controversially though, he was also reported to have originated in The Adventures of Mickey Mouse strip which began 1931. Thus the Duck has more “birthdays†than the Queen of England (plus the generally disUnited Kingdom and gradually diminishing Commonwealth) which probably explains why he’s such a bad-tempered old cuss.

Visually, Donald Fauntleroy Duck was largely the result of animator Dick Lundy’s efforts, and, with partner-in-fun Mickey Mouse, is one of TV Guide‘s 50 Greatest Cartoon Characters of All Time. The Duck has his own star on the Hollywood walk of fame and has appeared in more films than any other Disney player.

During the 1930s his screen career grew from background and supporting roles to a team act with Mickey and Goofy to a series of solo cartoons that began with 1937’s Don Donald, which also introduced love interest Daisy Duck and the nephews Huey, Louie and Dewey. By 1938 Donald was officially more popular than company icon Mickey Mouse, especially after his service as a propaganda warrior in a series of animated morale boosters and information features during WWII. The merely magnificent Der Fuehrer’s Face garnered the 1942 Academy Award (that’s an Oscar to you and me) for Animated Short Film…

Crucially for our purposes, Donald is also planet Earth’s most-published non-superhero comics character and has been blessed with some of the greatest writers and illustrators ever to punch a keyboard or pick up a pen or brush.

A publishing phenomenon and mega star across Europe – particularly Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, Greece, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Finland and Iceland – Donald & Co have spawned countless original stories and characters. Sales are stratospheric there and in the more than 45 other countries they export to. Japanese manga publishers have their own iterations too…

The aforementioned Silly Symphonies adaptation and Mickey Mouse newspaper strip guest shots were trumped in 1937 when Italian publisher Mondadori launched an 18-page story by Federico Pedrocchi in comic book format. It was quickly followed by a regular serial in Britain’s Mickey Mouse Weekly. The comic was produced under license by Willbank Publications/Odhams Press and ran from 8th February 1936 to 28th December 1957.

In #67 (May 15th 1937) it launched Donald and Donna (a prototype Daisy Duck girlfriend), drawn by William A. Ward. Running for 15 weeks it was followed by Donald and Mac before ultimately settling on Donald Duck, and a fixture until the magazine folded. The comic inspired similar Disney-themed publication across Europe with Donald regularly appearing beside company mascot Mickey…

In the USA, a daily Donald Duck newspaper strip launched on February 2nd 1938, with a colour Sunday strip added in 1939. Writer Ted Karp joined Taliaferro in expanding the duck cast, adding a signature automobile, dog Bolivar, cousin Gus Goose, grandmother Elvira Coot and expanded the roles of both Donna and Daisy…

In 1942, his licensed comic books canon began with the October cover-dated Dell Four Color Comics Series II #9 as Donald Duck Finds Pirate Gold: conceived by Homer Brightman & Harry Reeves, scripted by Karp and illustrated by Disney Studios employees Carl Barks & Jack Hannah. It was the moment everything changed…

Carl Barks was born in Merrill, Oregon in 1901, and raised in rural areas of the West during some of the leanest times in American history. He tried his hand at many jobs before settling into the profession that chose him. His early life is well-documented elsewhere if you need detail, but briefly, Barks was an animator before quitting in 1942 to work in the new-fangled field of comic books.

With studio partner Jack Hannah (another future strip illustrator) Barks adapted Karp’s rejected script for an animated cartoon short into Donald Duck Finds Pirate Gold, and although not his first published comics work, it was the story that shaped the rest of his career.

From then until his official retirement in the mid-1960s, Barks operated in self-imposed seclusion: writing, drawing and devising a vast array of adventure comedies, gags, yarns and covers that gelled into a Duck Universe of memorable and highly bankable characters. These included Gladstone Gander (1948), Gyro Gearloose (1952), Magica De Spell (1961) and the nefarious Beagle Boys (1951) to supplement Disney’s stable of cartoon actors. His greatest creation was undoubtedly the crusty, energetic, paternalistic, money-mad giga-gazillionaire Scrooge McDuck: the World’s wealthiest winged nonagenarian.

Whilst producing all that landmark material Barks was also just a working guy, generating cover art, illustrating other people’s scripts when asked, and contributing stories to the burgeoning canon of Duck Lore. After Gladstone Publishing began re-packaging Barks material amongst other Disney strips in the 1980s, he discovered the well-earned appreciation he never imagined existed…

So potent were his creations that they inevitably fed back into Disney’s animation output itself, even though his brilliant comic work was done for Dell/Gold Key and not directly for the studio. The greatest tribute was undoubtedly the animated series Duck Tales: heavily based on his classic Uncle Scrooge tales.

Barks was a fan of wholesome action, unsolved mysteries and epics of exploration, and this led to him perfecting the art and technique of the blockbuster tale: blending wit, history, plucky bravado and sheer wide-eyed wonder into rollicking rollercoaster romps that utterly captivated readers of every age and vintage. Without the Barks expeditions there would never have been an Indiana Jones…

During his working life Barks was blissfully unaware that his work (uncredited by official policy, as was all Disney’s comics output) had been recognised by a rabid and discerning public as “the Good Duck Artist.†When some of his most dedicated fans finally tracked him down, a belated celebrity began.

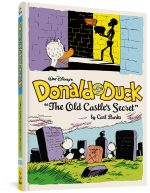

In 2013, Fantagraphics Books began chronologically collecting Barks’ Duck stuff in wonderful, carefully curated archival volumes, tracing his output year-by-year in hardback tomes and digital editions that finally do justice to the quiet creator. These will eventually comprise the Complete Carl Barks Disney Library. The physical copies are sturdy and luxurious albums – 193 x 261 mm – that would grace any bookshelf, with volume 6 re-presenting works from 1948 – albeit not in strict release order. I should also note that all the Four Color issues come from Series II of that mighty anthological vehicle and all cover are by Barks.

It begins eponymously with ‘The Old Castle’s Secret’ (FC #189, June 1948) as a crisis in the McDuck financial empire triggers a mission for Donald and the nephews: accompanying Scrooge to the ancestral pile in Scotland to search for millions in hidden treasure. Apparently the craggy citadel is haunted, but what they actually encounter is both more rationalistically dangerous and fantastically unbelievable…

Two single-page gags from the same issue follow, with ‘Bird Watching’ exposing the hidden perils of the hobby whilst superstition is painfully debunked in ‘Horseshoe Luck’ before ‘Wintertime Wager’ (Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories #88, January) introduces annoying cousin Gladstone Gander. Amidst chilling winter snows, the miraculously lucky, smugly irksome oik invites himself over for Christmas and soon he and Donald are involved in an escalating set of ordeals that might cost the Duck his house. Thankfully, Daisy and the boys are there to solve the problem…

Gainful employment was a regular dilemma for Donald and February’s ‘Watching the Watchman’ (WDC&S #89) finds him taking a midnight-to-daybreak job at the docks, but pitifully unable to alter his sleep patterns. Once again, Huey, Louie and Dewey offer outrageous assistance but this time it’s the Duck’s inability to stay awake that foils a million dollar heist….

They’re actually Donald’s rivals in ‘Wired’ (WDC&S #90, March) when all seek big bucks as telegram messengers. Sadly, millionaires are not generally friendly, welcoming or prone to giving giant gratuities…

A dedicated social climber, Donald plans a garden party in WDC&S #91 (April), but his notion of fancy dress and family solidarity utterly anger the boys, who retaliate with manic mesmerism in ‘Going Ape’, after which March of Comics #20 finds butterfly-hunter Donald at war with avaricious lepidopterist Professor Argus McFiendy across two continents.

Donald’s sharp and ruthless tactics inspire onlooker Sir Gnatbugg-Mothley to fund a safari to ‘Darkest Africa’ in search of the rarest butterfly on Earth. The daunting quest for the Almostus Extinctus is frenetically fraught, astoundingly action-packed and fabulously fun-filled but please be aware that despite Barks’ careful research and diligent, sensitive storytelling some modern folk could be upset by his depictions of indigenous peoples in terms of the accepted style of those decades-distant times.

Nevertheless, the bombastic war ends with a delicious sting in the tail.

In case you were wondering: March of Comics releases were prestigious promotional giveaways tied to retail products and commercial clients like Sears, combining licensed characters from across Whitman/KK/Dell’s joint catalogue. The often enjoyed print runs topping 5 million copies per issue. Being a headliner for them was a low key editorial acknowledgement of a creator’s capabilities and franchise’s pulling power…

Back in the regular world, Donald’s eternal war of nerves with the kids boiled over in FC #189 (June) as ‘Bean Taken’ saw his obsessive side dominant in a guessing game, a single-pager, preceding another exploring the downside of sandlot baseball in ‘Sorry to Be Safe’ (FC #199, October) and standard 10-page romp ‘Spoil the Rod’ (WDC&S #92, May). Here passing do-gooder Professor Pulpheart Clabberhead seeks to stop Donald’s apparent abuse of Huey, Louie and Dewey – but only until he gets to know them…

Although the science fiction boom and flying saucer mania was barely beginning in 1948, Barks was an early advocate and ‘Rocket Race to the Moon’ (WDC&S #93, June) sees newspaper seller Donald suckered into piloting an experimental lunar exploration ship. Tragically, Professors Cosmic and Gamma seem more concerned with a large cash-prize contest than advancing science and rival rocketman Baron De Sleezy is a ruthless schemer, but no one – not even the stowaway nephews – were prepared for what lived on the moon…

Patriotism inspires our bellicose birdbrain to enlist as ‘Donald of the Coast Patrol’ (WDC&S #94, July) but it’s his innate gullibility and bad temper that helps him bag a bunch of spies before true wickedness rears its downy head as ‘Gladstone Returns’ (WDC&S #95, August).

The ghastly Gander was designed as a foil for Donald, intended to be even more obnoxious than the irascible, excitable film fowl.

This originally untitled tale reintroduces him as a big noxious noise every inch as blustery a blowhard as Donald but still lacking his seemingly supernatural super-luck talent. Here, both furiously boast and feud, trying to one-up each other in a series of scams that does neither any good… especially once the nephews and Daisy join the battle…

Arguably Barks’ first masterpiece, ‘Sheriff of Bullet Valley’ was the lead tale from Dell Four Color Comics #199, drawing much of its unflagging energy and trenchant whimsy from Barks’ own love of cowboy fiction – albeit seductively tempered with his self-deprecatory sense of absurdist humour. For example, a wanted poster on the jailhouse wall portrays the artist himself, offering the princely sum of $1000 and 50¢ for his inevitable capture.

Donald is – of course – a self-declared expert on the Wild West (he’s seen all the movies) so when he and the boys drive through scenic Bullet Valley, a wanted poster catches his eye and his imagination. Soon he’s signed up and sworn in as a doughty deputy, determined to catch rustlers plaguing the locals. Unfortunately for him, the good old days never really existed and today’s bandits use radios, trucks, tommy guns and ray machines to achieve their nefarious ends. Can Donald’s impetuous boldness and the nephews’ collective brains and ingenuity defeat the ruthless high-tech raiders?

Of course they can…

That same issue first saw a brace of short gags, beginning with ‘Best Laid Plans’ as Donald’s feigned illness earns him extra hard labour rather than a malingering day in bed and closing with ‘The Genuine Article’ wherein suspicions of an antiques provenance leads to disaster…

The lads plans to go fishing are scuppered – but not for too long – when Donald demands their caddying services in ‘Links Hijinks’ (WDC&S #96, September). It all really goes south once Gladstone horns in and Donald’s competitive spirit overwhelms everybody…

That tendency to overreact informs ‘Pearls of Wisdom’ (WDC&S #97, October) when the nephews find a small pearl in a locally-sourced oyster and big-dreaming Donald goes overboard in exploiting the†hidden millions†probably peppering the ocean floor, before we close with another mission for Uncle Scrooge.

To close a deal with British toff Lord Tweeksdale, McDuck must prove his family pedigree by excelling in the most “asinine, stupid, crazy, useless sport in the worldâ€: fox hunting. Designating Donald his champion, the Downy Dodecadillionaire of Duckburg is thankfully unaware Huey, Louie and Dewey also consider themselves ‘Foxy Relations’ (WDC&S #98, November), injecting themselves covertly into proceedings with catastrophic repercussions…

The visual verve over, we move on to validation as ‘Story Notes’ offers commentary for each Duck tale and Donald Ault relates ‘Carl Barks: Life Among the Ducks’, before ‘Biographies’ explain why he and commentators Alberto Beccatini, R, Fiore, Craig Fischer, Jared Gardner, Leonardo Gori, Rich Kreiner, Ken Parille, Stefano Priarone, Francesco (“Frankâ€) Stajano and Mattias Wivel are saying all those nice and informative things.

We close with an examination of provenance as ‘Where Did These Duck Stories First Appear?’ explains the somewhat byzantine publishing schedules of Dell Comics.

Carl Barks was one of the greatest exponents of comic art the world has ever seen, and almost all his work featured Disney’s Duck characters: reaching and affecting untold millions of readers across the world and he all too belatedly won far-reaching recognition. You might be late to the party but it’s never too soon to climb aboard the Barks Express.

Walt Disney’s Donald Duck “The Old Castle’s Secret†© 2013 Disney Enterprises, Inc. All contents © 2013 Disney Enterprises, Inc. unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.