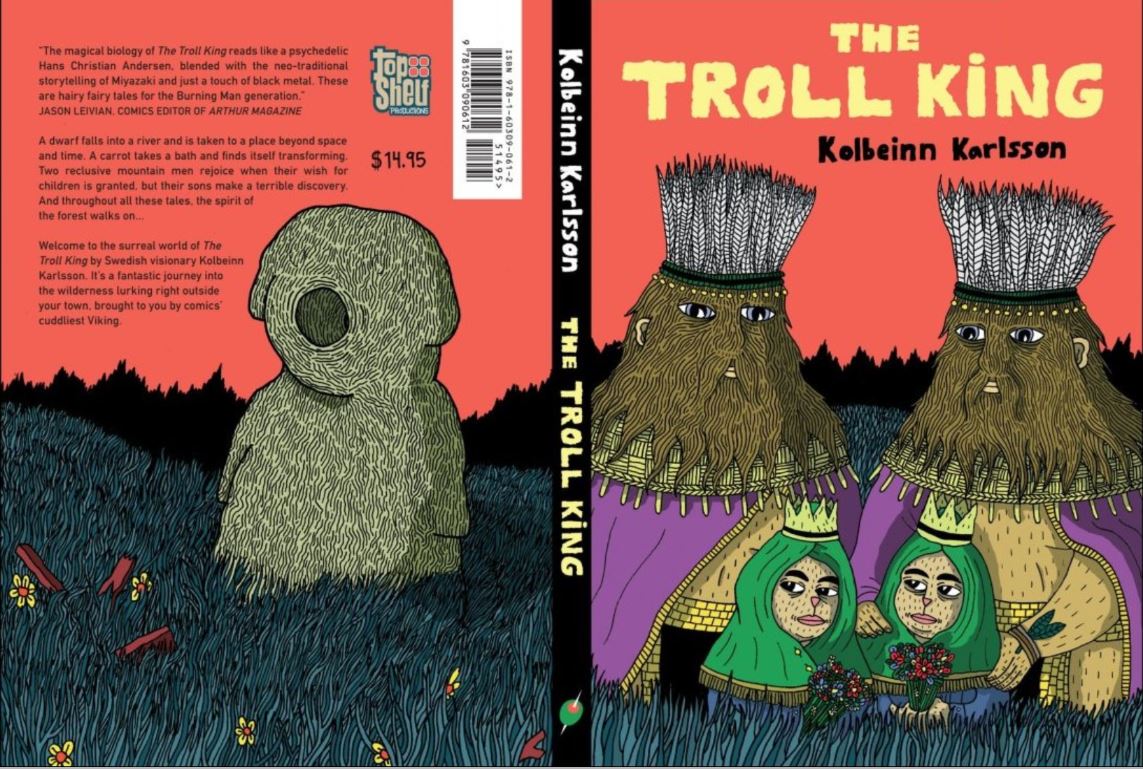

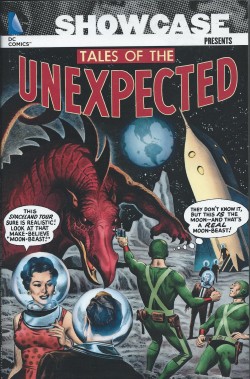

By Otto Binder, France E. Herron, Jack Miller, Dave Wood, Bernard Baily, Bob Brown, Nick Cardy, Bill Ely, Bill Draut, Jack Kirby, Mort Meskin, Sheldon Moldoff, Jim Mooney, Ruben Moreira, George Papp, John Prentice, George Roussos, Leonard Starr & various (DC Comics)

ISBN: 978-1-4012-3520-8

American comicbooks started rather slowly until the invention of superheroes unleashed a torrent of creative imitation and established a new entertainment genre. Implacably vested in World War Two, the Overman swept all before him (occasionally her or it) until the troops came home and the more traditional themes and heroes resurfaced and eventually supplanted the Fights ‘n’ Tights crowd.

Whilst a new generation of kids began buying and collecting, many of the first fans also retained their four-colour habit but increasingly sought older themes in the reading matter. The war years had irrevocably altered the psychological landscape of the readership, and as a more world-weary, cynical young public came to see that all the fighting and dying hadn’t really changed anything, their chosen forms of entertainment (film and prose as well as comics) increasingly reflected this.

As well as Western, War and Crime comics, celebrity tie-ins, madcap escapist comedy and anthropomorphic funny animal features were immediately resurgent, but gradually another of those cyclical revivals of spiritualism and a public fascination with the arcane led to a wave of impressive, evocative and shockingly addictive horror comics.

There had been grisly, gory and supernatural stars before, including a pantheon of ghosts, monsters and wizards draped in mystery-man garb and trappings (the Spectre, Mr. Justice, Frankenstein, The Heap, Zatara, Dr. Fate and dozens of others), but these had been victims of circumstance: The Unknown as a power source for super-heroics. Now the focus shifted to ordinary mortals thrown into a world beyond their ken with the intention of unsettling, not vicariously empowering, the reader.

Almost every publisher jumped on an increasingly popular bandwagon, with B & I (which became magical one-man-band Richard E. Hughes’ American Comics Group) launching the first regularly published horror comic in the Autumn of 1948. Technically speaking, however, Adventures Into the Unknown was pipped at the post by Avon who had released an impressive single issue entitled Eerie in January 1947; later reviving the title by launching a regular series in 1951. All the meanwhile, parents’ favourite Classics Illustrated had long been milking the literary end of the genre with adaptations of the Headless Horseman, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (both 1943), The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1944) and Frankenstein (1945) among others.

As long as we’re keeping score, this was also the period in which Joe Simon & Jack Kirby identified another “mature market†gap and invented Romance comics (Young Romance #1, September 1947) but they too saw the sales potential for spooky material, resulting in the seminal Black Magic (1950) and boldly obscure psychological drama anthology Strange World of Your Dreams (1952).

The wholesome family company that would become DC Comics bowed to the inevitable and launched a comparatively straight-laced anthology that nevertheless became one of their longest-running and most influential titles with the December 1951/January 1952 launch of The House of Mystery. Its success led to a raft of such creature-filled fantasy compendiums in the years that followed such as Sensation Mystery, My Greatest Adventure, House of Secrets and, in 1956 – during a boom in B-Movie science fiction thrillers – Tales of the Unexpected…

A hysterical censorship scandal which led to witch-hunting hearings (check out Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency, April-June 1954 on your search engine of choice) was derailed by the industry adopting a castrating straitjacket of draconian self-regulatory rules. Horror titles produced under the aegis and emblem of the Comics Code Authority were sanitised and anodyne affairs in terms of Shock and Gore, even though the market’s appetite for suspense and the uncanny was still high. Stories were dialled back into marvellously illustrated, rationalistic, fantasy-adventure vehicles which dominated until the 1960s when super-heroes (which had begun to creep back after Julius Schwartz reintroduced the Flash in Showcase #4, 1956) finally overtook them.

This mammoth monochrome compilation (still tragically unavailable in colour or in digital editions) offers a stunning voyage to the fantastic outer limits of 1950s imagination, collecting the first 20 issues of the charmingly enthralling anthology – produced under the watchful eyes of the Comics Code Authority – which spans cover dates February/March 1956 to December 1957 and starts with a quartet of intriguing, beautifully rendered pocket thrillers.

Sadly for me and you, records are spotty and many of the authors remain unsung (although possible candidates include Dave Wood, Bill Finger, Ed Herron, Joe Samachson, George Kashdan, Jack Miller and Otto Binder and I’ll just guess whenever I’m more than half-certain) but the pictorial pioneers at least can be deservedly celebrated…

Behind a captivating cover by Bill Ely, Tales of the Unexpected #1 opens our uncanny excursions with ‘The Out-of-The-World Club’, drawn by the astoundingly precise John Prentice, detailing the unearthly secret of a night-spot offering truly original groovy sounds, whilst ‘The Dream Lamp’, limned by Leonard Starr, takes a bucolic glance at a device which seems able to perform impossible feats.

Jack Miller, Howard Purcell & Charles Paris then ironically reveal ‘The Secret of Cell Sixteen’ which fools yet one more prisoner in the Bastille, after which the debut issue ends with a bleak alien invasion fable in ‘The Cartoon that Came to Life’ by Otto Binder & Bill Ely.

Issue #2 offered the uncredited conundrum of ‘The Magic Hats of M’sieu La Farge’ (art by Ruben Moreira) involving ordinary folk impelled to perform extraordinary feats when wearing the titfers of famous dead folk, whilst ‘The Fastest Man Alive’ (drawn by Bill Draut & Mort Meskin) discloses how an obsessive rivalry brings destruction upon a man forever relegated to second best behind his exceptional greatest friend…

‘The Record of Doom’ (Ely art) apparently drives listeners to suicide until a canny cop uncovers the truth, but ‘The Gorilla who Saved the World’ (Starr) is as incredible and alien as you’d expect in a tale of sharp sci-fi suspense…

Issue #3 opened with Purcell’s ‘The Highway to Tomorrow’ wherein a motorway through Native American sacred lands almost results in a new uprising, after which Meskin’s ‘The Man Nobody Could See’ revisits the old plot of an invisible criminal. ‘I Lost My Past’ (art by Mort Drucker) recounts an implausibly complex scheme to cure an amnesiac before ‘The Man with 100 Wigs’ (Miller & Prentice), provides a genuinely compelling mystery about a petty thief who steals a sorcerer’s chest filled with hairpieces that impart bizarre powers to the wearer…

The mix of cop stories, aliens and the arcane acts clearly struck a popular chord as, with Tales of the Unexpected #4, the comic was promoted to monthly. ‘Seven Steps to the Unknown’ (Ely) continued the eclectic winning formula through a perilous puzzle regarding a group of complete strangers inexplicably linked and targeted for murder, whilst ‘The Day I Broke All Records’ – illustrated by Sheldon Moldoff – follows a top athlete who gains something “extra†after finding an elixir once favoured by unbeatable Roman gladiator Apulius…

Then a murderer is brought to justice after becoming obsessed with ‘The Flowers of Sorcery’ (Starr) whilst ‘The House Where Dreams Come True’ (Prentice) offers a far kinder tale of human generosity to melt the heart of the most jaded reader.

In #5 ‘The Man Who Laughed at Locks’ (Moreira) discloses the inevitable fate of a cheat when rival inventors clash; ‘I Was Bewitched for a Day’ (Ely) reveals how easily domestic reality can be overturned, and Moldoff portrays the bewilderment of an Art Investigator faced with ‘The Living Paintings’ before Miller & Prentice again triumph with the tale of an actor literally possessed by his role in ‘The Second Life of Geoffrey Hawkes’…

TotU #6 opens with ‘The Telecast from the Future’ (drawn by George Papp) wherein a technician foolishly convinces himself that his gear hasn’t really opened a peephole into tomorrow, whilst Ely’s ‘Dial M for Magic’ focusses on a prestidigitator’s club that auditions an amazing applicant who doesn’t just do “tricksâ€â€¦

‘The Forbidden Flowers’ (Moldoff) then exposes a killer who thinks himself safe, after which Moreira’s ‘The Girl in the Bottle’ leads an unsuspecting oceanographer into fantastic peril… and another incredible criminal scam.

Golden Age great Bernard Baily joins the rotating art crew with #7 as ‘The Pen that Never Lied’ visits a number of people, dispensing justice through unvarnished truth, after which ‘Beware, I Can Read your Mind!’ (Moldoff) depicts a telepath discovering the overwhelming cost of his gift.

When a miner finds a talking talisman, it promises anything except ‘The Forbidden Wish’ (George Roussos). Tragically it was the only thing the weak-minded man wanted…

The issue closes with the art debut of the astounding Nick Cardy who lovingly detailed the fate of a murderous thug who refused to listen to the sage advice of ‘The Face in the Clock!’

Tales of the Unexpected #8 opens with fantastic fantasy as ‘The Man Who Stole a Genie’ (Meskin) slowly succumbs to greed and mania, whilst ‘The Secret of the Elephant’s Tusk’ (Ely art) follows the trail of death resulting after a poacher kills a sacred pachyderm. Roussos’ ‘The Four Seeds of Destiny’ chillingly reveals the doom that comes to a TV reporter who stole relics from a Pharaoh’s tomb before ‘The Camera that Could Rob’ (Starr) proves that, even for a thief with an unbeatable gimmick, mistreating a cat never ends well…

In issue #9 ‘The Amazing Cube’ (possibly scripted by George Kashdan and definitely limned by Baily) sees an unscrupulous gambler falling foul of his own handmade dice, whilst a killer conman gets his comeuppance courtesy of ‘The Carbon Copy Man’ (Papp). ‘The Day Nobody Died’ by Roussos is a classic of moody mystery wherein a doctor pursues a dark stranger and regrets catching him, after which a little lad saves the world from alien invasion and know-it-all adults in Starr’s ‘The Man Who Ate Fire’.

The tone of the time was gradually turning and oppressive occultism was slowly succumbing to the Space Age lure of weird science as TotU #10 proved with ‘The Strangest Show on Earth’ (art by Jim Mooney) wherein a bankrupt showman stumbles over a Martian circus. Sadly, the bizarre performers had their own agenda to adhere to…

‘The Phantom Mariner’ (Moldoff) follows an obsessed sea captain to his inescapable fate, before a scientist faces a deadly dilemma after creating ‘The Duplicate Man’ (Ely) and Meskin reveals how an antique collector’s compulsion endangers his life in ‘I Was Slave to the Wizard’s Lamp’…

A criminal inventor pays the ultimate price for his venality in the Baily-limned ‘Who Am I?’ which opened Tales of the Unexpected #11, whilst ‘I Was a Man from the Future’ (Cardy) sees an American mountaineer stumble through a time-warp into adventure and romance in 15th century France and ‘The Ghost of Hollywood’ (Ely) confounds a special effects designer determined to debunk it.

Starr then closed out the issue with ‘The Man Who Hated Green’, as an artist embarks on an extraordinary campaign of terror…

Issue #12 began with Cardy’s tale of a quartet of escaped convicts terrorising three little old ladies and subsequently cursed by ‘The Four Threads of Doom’, after which ‘The Witch’s Statues’ (Meskin) proves to be more scurrilous scam than sinister sorcery.

Following a downturn in the industry, Jack Kirby briefly returned to National/DC at this time: producing a mini-bonanza of mystery tales and drawing Green Arrow, all whilst preparing his newspaper strip Sky Masters of the Space Force.

He also re-packaged for Showcase an original team concept kicking around in his head since he and Joe Simon had closed the innovative but unfortunate Mainline Comics. Blending explosive adventure with the precepts of mystery comics, Challengers of the Unknown became the template for the entire Silver Age superhero resurgence…

After years of working for others, Simon & Kirby had established their own publishing company, producing comics for a more sophisticated audience, only to find themselves in a sales downturn and awash in public hysteria generated by the aforementioned anti-comic pogrom of US Senator Estes Kefauver and psychologist Dr. Fredric Wertham.

Simon quit the business for advertising, but Kirby soldiered on, taking his skills and ideas to a number of safer, if less experimental, companies. Here his run of short fantastic suspense tales commences with ‘The All-Seeing Eye’ (possibly scripted by Dave Wood?) wherein a journalist responsible for many impossible scoops realises that the ancient artefact he employs is more dangerous than beneficial…

The issue ends with Ely’s rousing thriller ‘The Indestructible Man’ wherein a stuntman with innate invulnerability decides to get rich quick, no matter who gets hurt…

In #13, an amnesiac retraces his lost past by seeking out ‘Weapons of Destiny’ (perhaps Binder with Ely art), whilst Meskin’s ‘The Thing from the Skies’ initially proves a boon but ultimately the downfall for a murdering conman. A ghostly ‘Second Warning’ (Papp) saves a tourist when he visits battlefields of WWII, after which France E. Herron & Cardy’s ‘I Was a Prisoner of the Supernatural’ reveals how an actor escapes a deal with the devil before Herron & Kirby steal the show with a grippingly devious crime-caper in ‘The Face Behind the Mask’…

Tales of the Unexpected #14 starts with Meskin’s ‘The Forbidden Game’ as an embezzler plays fast and loose with a wagering wizard, and is followed by ‘Cry, Clown, Cry’ (Baily) which sees a baffled son ignore his father’s injunction not to follow the family tradition to be a gag-man…

Papp pictures the fate of a swindler who wants folk to believe he is ‘The Man Who Owned King Arthur’s Sword’ and Moldoff finishes up proceedings as a crook is haunted by ‘The Green Gorilla’ manifested by his misdeeds.

Kirby led off in #15, his ‘Three Wishes to Doom’ proving that even with a genie’s lamp crime does not pay, after which ‘The Sinister Cannon’ (Baily) employed by an insidious alien infiltrator proves far more than it appears. ‘The Rainbow Man’ (Roussos) is a scientific bandit who overestimates the efficacy of his camouflage discovery and ‘The City of Three Dooms’ – by Meskin – wraps up things with a mesmerising time-travel romp featuring Nazi submariners on a voyage to infinity…

There’s an inexplicable frisson in Kirby’s ‘The Magic Hammer’ which opens #16 as the King of Comics here relates how a prospector finds a mallet capable of creating storms and goes into the rainmaking business… until the original owner turns up…

That superb vignette is augmented by ‘I Was a Spy for Them’ (Meskin) as a canny physicist turns the tables on the star men who captured him, a crooked archaeologist gains unbeatable power from an ancient ring but becomes ‘The Exile from Earth’ (Dave Wood & Moldoff), and Moreira illustrates ‘The Interplanetary Line-Up’, wherein an actual Man from Mars gatecrashes a science fiction writer’s fancy dress party…

In #17 ‘Who is Mr. Ashtar?’ (Kirby) chillingly follows a hotel detective who just knows there’s something off about the new guest in Room 605, whilst ‘Beware the Thinking Cap’ (Ely) describes the rise and fall of a crook who finds the device which inspired all the geniuses of history. Baily illustrates how a lifer in jail uses a unique method of escape in ‘The Bullet Man’, and the issue ends on ‘The Impossible Voyage’ (Mooney) as a couple of alien pranksters take earth suckers for a ride on what only looks like a fairground attraction…

Mooney takes lead spot in #18 as ‘The Man Without a World’ rejects Earth only to learn that a life in space is no life at all, after which Meskin’s ‘The Riddle of the Glass Bubble’ threatens to end all life until a little kid finds an unlikely solution. Cardy opens ‘The Amazing Swap Shop’, where humans trade “junk†for impossibly useful gadgets before Kirby shows how a clever human saves us all by outwitting ‘The Man Who Collected Planets’.

By now thoroughly gripped in UFO fever, Tales of the Unexpected #19 began with ‘The Man from Two Worlds’ (Cardy) wherein nasty Neptunians attempt to abduct an Earth scientist by guile, whereas ‘D-Day on Planet Vulcan’ (Mooney) envisages embattled ETs begging our help to end a world-crushing crisis, after which a meteor turns a hapless technician into ‘The Human Lie Detector’ (Ely) and a dotty old eccentric surprises everybody by ending ‘The Menace of the Fireball’ (with art by Bob Brown).

This terrific tome concludes with issue #20 where ‘The Earth Gladiator’ (Cardy) struggles to save his life and prove Earth worthy of continued existence, an engineer scuppers ‘The Remarkable Mr. Multiplier’ (Ely) before his invention wrecks civilisation and Baily illustrates that not every alien incursion is malign or dangerous in ‘I Was Marooned on Planet Earth’…

Moreira then brings the cosmic catalogue to a close with ‘You Stole Our Planet’ wherein gigantic space creatures arrive with a strong claim of prior ownership…

Although certainly dated and definitely formulaic, these complex yet uncomplicated suspenseful adventures are drenched in charm, gilded in ingenuity and still sparkle with innocent wit and wonder. Perhaps not to everyone’s taste nowadays, these fantastic exploits are nevertheless an all-ages buffet of fun, thrills and action no fan should miss.

© 1956, 1957, 1958, 2012 DC Comics. All Rights Reserved.