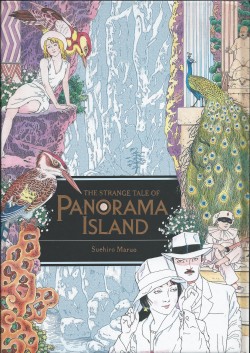

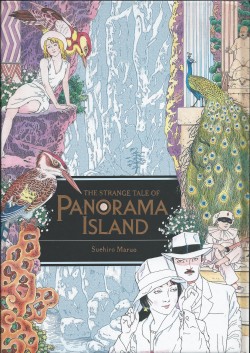

By Edogawa Rompo, adapted and illustrated by Suehiro Maruo, translated by Ryan Sands & Kyoko Nitta (Last Gasp)

ISBN: 978-0-86719-777-8 (HB)

Edogawa Rompo is revered as the Godfather of Japanese detective fiction – his output as author and critic defining the crime thriller from 1923 to his death in 1965. Born TarÅ Hirai, he worked under a nom-de-plume based on his own great inspiration, Edgar Allen Poe, penning such well-loved classics as The Two-Sen Copper Coin, The Stalker in the Attic, The Black Lizard and The Monster with 20 Faces as well as many tales of his signature hero detective Kogoro Akechi, notional leader of the stalwart young band ShÅnen tantei dan (the Boy Detective’s Gang).

He did much to popularise the concept of the rationalist observer and deductive mystery-solver. In 1946, he sponsored the detective magazine HÅseki (Jewels) and a year later founded the Detective Author’s Club, which survives today as the Mystery Writers of Japan association.

Although his latter years were taken up with promoting the genre, producing criticism, translation of western fiction and penning crime books for younger audiences, much of his earlier output (Rampo wrote 20 novels and lots of short stories) were dark, sinister concoctions based on the trappings and themes of ero guro nansensu (“eroticism, grotesquerie, and the nonsensicalâ€) playing into the then-contemporary Japanese concept of hentai seiyoku or “abnormal sexualityâ€.

From that time comes this particular adaptation, originally serialised in Enterbrain’s monthly magazine Comic Beam from July 2007-January 2008.

Panorama-tÅ Kidan or The Strange Tale of Paradise Island was a prose vignette released in 1926, adapted here with astounding flair and finesses by uncompromising illustrator and adult manga master Suehiro Maruo.

A frequent contributor to the infamous Japanese underground magazine Garo, Maruo is the crafter of such memorable and influential sagas as Ribon no Kishi (Knight of the Ribbon), Rose Coloured Monster, Mr. Arashi’s Amazing Freak Show, The Laughing Vampire, Ultra-Gash Inferno, How to Rake Leaves and many others.

This is a lovely book. A perfect physical artefact of the themes involved, this weighty oversized (262x187mm) monochrome hardback has glossy full-colour inserts, creator biographies and just feels like something extra special, whilst it compellingly chronicles an intriguingly baroque tale of greed, lust, deception and duplicity which begins when starving would-be author Hitomi Hirosuke reads of the death of the Taisho Emperor. Sadly, it still hasn’t made it into digital formats yet…

On December 26th 1926, Japan suffered a social catastrophe. The shock of losing the revered ruler reverberated through the entire nation. The trauma forced one failing writer to reassess his life. He finds himself wanting…

At another fruitless meeting with his editor Ugestu, Hitomi learns that an old friend, Genzaburo Komoda, has passed away. At college the boys were implausibly inseparable: the poor but ambitious kid and the heir to one of the greatest industrial fortunes in Japan. Perhaps it was because they looked and sounded exactly alike: doppelgangers nobody could tell apart…

The presumed cause of death was the asthma which had plagued the wealthy scion all his life and Hitomi, fuelled by self-loathing and inspired by Poe’s tale “The Premature Burialâ€, hatches a crazy scheme…

Faking his own suicide the writer leaves his effects to Ugestu before travelling to Kishu and immediately beginning his insane plot. Starving himself the entire time, Hitomi locates his pal’s grave, disposes of the already mouldering body and dons the garments and jewellery of Komoda. He even smashes out a front tooth and replaces it with the false one from the corpse…

His ghastly tasks accomplished, the starving charlatan simply collapses in a road where he can be found…

The news spreads like wildfire and soon all Komoda’s closest business associates have visited the miraculous survivor of catalepsy. The intimate knowledge Hitomi possesses combined with the “shock and confusion†of his miraculous escape is enough to fool even aged family retainer Tsunoda, and the fates are with him in that the widow Chiyoko has gone to Osaka to get over her loss. Of course she will rush back as soon as she hears the news…

However with gifts and good wishes flooding in, even Chiyoko is seemingly fooled and the fraudster begins to settle in his new skin. Just to be safe, however, he keeps the wife at a respectful and platonic distance. Comfortably entrenched, he begins to move around the Komoda fortune.

Hitomi the starving writer’s great unfinished work was The Tale of RA, a speculative fantasy in which a young man inherits a vast fortune and uses it to create an incredible, futuristic pleasure place of licentious delight. Now the impostor starts to make that sybaritic dream a reality, repurposing the family wealth into buying an island, relocating its inhabitants and building something never before conceived by mind of man…

Fobbing off all questions with the lie that he is constructing an amusement park that will be his eternal legacy, he populates the marvel of Arcadian engineering, landscaping, and optical science with a circus of wanton performers, living statues of erotic excess and a manufactured mythological bestiary.

He even claims that the colossal expenditure will begun healing the local economic malaise, but for every obstacle overcome another seems to occur. Moreover he cannot shift the uneasy feeling that Chiyoko suspects the truth about him…

Eventually however the great dream of plutocratic grandeur, lotus-eating luxury and hedonistic sexual excess is all but finished and “Komoda†escorts his wife on a grand tour of the wondrous celebration of debauched perversity that is his personal empire of the senses.

Once ensconced there he ends his worries of Chiyoka exposing him, but all too soon his Panorama Island receives an unwanted visitor.

Kogoro Akechi has come at the behest of the wife’s family and he has a few questions about, of all things, a book.

It seems that an editor, bereaved by the loss of one of his protégés, posthumously published that tragic young man’s magnum opus to celebrate his wasted life: a story entitled The Tale of RA…

This dark compelling morality play is realised in a truly breathtaking display of artistic virtuosity from Maruo, who combines clinical detail of intoxicating decadence with vast graphic vistas in a torrent of utterly enchanting images, whilst never allowing the visuals to overwhelm the underlying narrative and rise and fall of a boldly wicked protagonist…

Stark, stunning, classically clever and utterly adult The Strange Tale of Paradise Island is one of the best-looking, most absorbing crime thrillers I’ve seen this century, and no mystery loving connoisseur of comics, cinema or prose should miss it.

© 2008, 2013 HIRAI Rutaro, MARUO Suehiro. All rights reserved. English translation © 2013 Last Gasp.